Buying an electric car is initially pricier, but its operational costs are lower compared to a conventional vehicle, correct?

If you prefer a simple answer, the response is ‘yes’. However, the situation is more complex, with the cost of charging an electric vehicle generally being less than refueling a petrol or diesel car.

A more nuanced but truthful answer would be ‘it depends’. Rising energy prices can make home charging more costly than before, yet it remains significantly cheaper than utilizing public charging stations. If you need to recharge while away from home, an electric vehicle might not save you much compared to filling up a petrol or diesel car. Depending on how you calculate the expenses, it’s possible you won’t save anything at all.

We have been crunching numbers to assist you in figuring out the expenses associated with charging an electric vehicle both at home and on the go when using public chargers.

To keep things straightforward, our calculations assume charging sessions involve filling the car’s batteries from 0% to 100%. However, this isn’t commonly how it works because allowing a battery to drop to 0% is similar to running out of petrol, and charging to 80 or 90% helps maintain battery longevity.

What is the cost of charging an electric car at home?

This varies based on two factors. The first is your energy tariff at home – some are designed specifically for electric vehicle owners. The second factor is the capacity of your car’s high-voltage battery. The bigger the battery, the more electricity it consumes to charge, and the higher your costs will be.

Before purchasing your first electric vehicle, it would be wise to have a wallbox home charger installed.

Cost of home wallboxes

Although you can charge an electric vehicle using a regular socket in a pinch, it’s not the ideal method. Domestic three-pin plugs aren’t recommended for EV charging because they charge slowly and may put too much strain on the socket, raising safety concerns.

Three-pin plugs typically charge at around 2.3 kiloWatts (kW), meaning that a 100 kiloWatt hour (kWh) battery will take 43.5 hours to charge from full to empty. If you plug it in on a Saturday morning, it would barely be ready for the beginning of the following week on Monday.

Fortunately, several manufacturers provide home wallbox chargers, giving ample options. They start at around £800. Importantly, these are specifically engineered for safely charging electric vehicles and can generally supply electricity at up to 7kW, which reduces the charging time to less than half.

If your home has a three-phase electricity connection, you can install a more powerful 11kW charger, but most residences in the UK have single-phase connections.

Regardless, you need off-street parking or a garage to install a wallbox.

Pricing for energy tariffs

Investing in a wallbox is a one-time expense, while your home energy prices will significantly impact how much it costs to charge an electric car at home.

EV battery sizes are expressed in kiloWatt hours (kWh), just like the electricity supplied to your home. It’s straightforward to determine that charging a 100kWh battery requires 100kWh of electricity to fill it from 0-100%, and you can compute the cost by checking the price per kWh from your energy supplier.

As of October 1 to December 31, 2024, the energy price cap for households on a standard variable tariff is £0.245 per kWh; at this rate, charging a 100kWh EV will cost £24.50 from 0-100%.

If your EV has a 50kWh battery, these costs can be halved, whereas an 80kWh EV would entail 80% of those expenses (approximately £19.60 at £0.245 per kWh).

Cost per mile is a crucial metric

While the rate your energy provider charges per unit plays a significant role in your electric vehicle’s running costs, the efficiency of the EV is also crucial.

The 100kWh EV modeled earlier can store double the energy compared to a 50kWh vehicle. Under similar conditions, that means it would have twice the range; however, it’s important to note that many EVs with larger batteries tend to be heavier than their smaller counterparts.

Consequently, smaller EVs often achieve greater distances on a single kWh of energy. For instance, a highly efficient electric vehicle might travel five miles for each kWh its battery holds, while a less efficient model may only go 2.5 miles per kWh.

Thus, the more efficient EV will cost you half as much per mile compared to the less efficient one. Therefore, although the expenses for charging each vehicle will differ, the cost to travel a mile in each is significantly more relevant.

The size of the battery plays a role in determining the car’s price. Models of the same electric vehicle (EV) with larger batteries tend to be pricier and less efficient. This is something to keep in mind if you’re considering spending more on an EV that boasts a larger battery and extended range.

An EV that achieves 2.5 miles per kilowatt-hour (kWh) when charged at an electricity rate of £0.245 per kWh will cost nearly £0.10 for each mile driven.

In contrast, an EV that accomplishes 5 miles per kWh charged at the same rate will have a cost of slightly under £0.05 per mile.

Comparatively, a petrol vehicle that gets 40 miles per gallon will have a cost per mile of £0.155, based on the average price of unleaded petrol (as of September 2024) at £1.3615 (around £6.19 per gallon). This is three times the cost-per-mile of a highly efficient EV and one and a half times more than a less efficient one.

Specialized home EV tariffs

Electricity providers often do not charge the maximum allowable under the price cap, especially for customers who opt for a tariff tailored for EV users.

These tariffs usually offer significantly lower rates during nighttime hours, and with many EVs (along with numerous home wallboxes) capable of scheduling charging based on user settings, you can easily take advantage of these off-peak rates.

For instance, Octopus Energy’s Flexible Octopus tariff charges £0.2313 per kWh (just over 23p), which is already lower than the price cap. If you switch to the Intelligent Octopus Go tariff, the price falls to merely £0.07 for six hours each night. Under this tariff, fully recharging a 100kWh EV battery would set you back just £7, resulting in savings of £16.13 compared to charging with the regular Flexible Octopus tariff.

Notably, the same reduced energy price applies throughout your home during those six hours, which is beneficial for night owls wanting to binge-watch shows or catch up on laundry while others are asleep.

What is the cost to charge an electric vehicle at a public charging station?

If you’ve managed to read this far, the good news is the next part is much more straightforward. No need to think about wallboxes or varying tariffs with public charging; most of the charging principles and costs have already been discussed.

In summary, the cost of charging a public electric vehicle is based on the size of its battery and the electricity price.

Unfortunately, public charging stations generally cost more than home charging options. Each network sets its own prices, similar to how petrol stations operate.

For example, the Ionity network charges £0.74 per kWh, meaning a 100kWh EV would require £74 to charge from fully drained to fully charged, while a 50kWh EV would run £37.00. An EV that can travel five miles per kWh will cost 14.8 pence per mile using Ionity, while one that achieves 2.5 miles per kWh will cost 29.6 pence.

Instavolt chargers cost £0.85 per kWh, leading to a full charge costing £85 for a 100kWh EV from empty.

As of September 2024, Osprey has a rate of £0.79 per kWh for its rapid chargers; charging a 100kWh EV from empty to full would thus cost £79.

BP Pulse charges between £0.44 and £0.85, depending on both the speed of the charger you choose and whether you are a subscriber or a one-time user.

You might get lucky—some public EV charging points are free to use, typically found in locations such as supermarkets, gyms, and hotels. Generally, these free chargers are of the slower 7kW type, unlike the rapid 50-150kW chargers available at most public paid stations.

You can locate your nearest charging station using a useful electric car charging point map. If you own a Tesla, there’s also a dedicated Tesla charging stations map available.

What is the cost to charge an electric car on the motorway?

Charging an electric vehicle at a motorway service station may cost more than at public charging points in urban areas—similar to how filling up a petrol or diesel car is pricier at motorway service areas—though some charging networks have flat rates regardless of the location.

Motorway service stations usually feature a larger number of rapid chargers compared to other spots, allowing you to gain substantial range for your money while enjoying a coffee and croissant. Be aware, however, that certain chargers and motorway service car parks may impose time restrictions, which can incur fines for overstaying.

Tesla Superchargers

If you drive a Tesla, you can utilize the company’s Supercharger network. This network is gradually being opened (on a trial basis) to other EV owners, but it primarily remains exclusive to Tesla drivers.

Tesla Superchargers are available at numerous locations, including many services along motorways. They are typically very quick, often featuring 150kW points that can charge a battery from empty to full in approximately 40 minutes for the latest models.

The cost to use Superchargers varies by site and is shown on the vehicle’s touchscreen, so it’s advisable to check the price before connecting. Earlier Tesla models included free Supercharger access, but this was discontinued for vehicles manufactured after 2016, which now receive a limited amount of mileage credits or hours of free charging each year.

Despite the higher upfront costs of electric vehicles compared to gasoline cars, battery-electric vehicles have generally been more economical to own and operate in the long run.

This is mainly because recharging has traditionally been significantly cheaper than refuelling, making electric vehicle (EV) ownership financially beneficial after a couple of years.

This used to be an undeniable truth—at least until recently.

The ongoing energy crisis in Europe, driven by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and threats to gas supplies, has not only raised concerns about frigid winters but also skyrocketed electricity prices, largely due to the high reliance on gas for power generation.

Conversely, oil supply has been less impacted, and numerous European nations have been heavily subsidizing petrol and diesel.

In September 2022, the average household in the EU faced a staggering 72% increase in the cost per kWh of electricity compared to the previous year.

During the same period, aided by government subsidies, fuel prices at the pump rose less significantly: with diesel increasing by 36% and petrol by just 15%.

The unprecedented spikes in electricity costs have cast doubt on the assumption that recharging is cheaper than refuelling, with some forecasts suggesting that the shift toward e-mobility could suddenly stall.

However, even amid significant market disruption, recharging remains, on average, considerably cheaper than refuelling.

But is the situation genuinely as bleak as it seems?

The brief answer is no. Even amidst significant market disruption, recharging, on average, remains far less expensive than filling up.

The detailed answer is less straightforward.

The influence of fuel subsidies plays a role in this situation.

One reason for the low prices of diesel and petrol is the existence of fuel tax subsidies.

In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the resulting spike in petrol and diesel costs, many countries began artificially lowering the prices for consumers through extensive subsidies.

It was projected that in 2022, EU nations would spend over €27 billion to reduce the price per litre by more than 30 cents in certain cases. In some regions, this has effectively returned prices to, or even below, their pre-crisis levels.

Charging electricity can occasionally be pricier than petrol or diesel when using a super-fast charger on a busy motorway.

However, according to the European Commission, the vast majority—nine out of ten—of EVs are charged at home, at work, or at other private charging stations. This method of charging is typically the most affordable.

Interestingly, charging via a slow AC charger, especially with a monthly or annual subscription, remains a fraction of the cost of refuelling your vehicle—even today.

It’s essential to note that the majority of EVs are charged at home, at work, or at other private locations, according to the European Commission, where this charging approach is usually the least expensive.

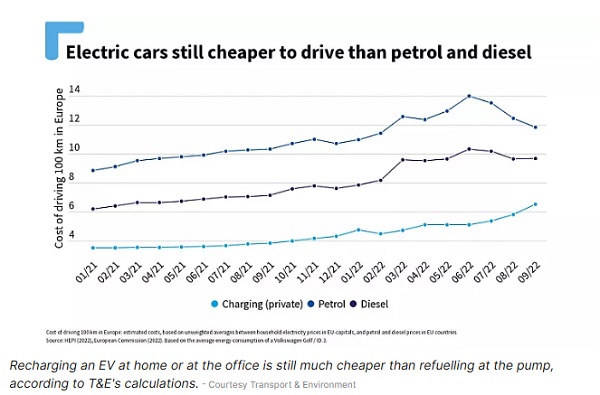

According to a T&E analysis of household electricity prices across EU capitals (as national prices updated aren’t available) and weekly petrol and diesel rates, using an average electric car to travel 100 kilometres in September 2022 cost approximately €6.50 when charged at home.

Driving the same distance in a petrol vehicle was roughly 80% more expensive, while the cost with a diesel car was about 50% higher.

However, these costs do not apply uniformly across all countries.

In nations like Italy and Germany, where electricity costs are among the highest in Europe—due to dependence on gas—the differences were minimal, at least in comparison to diesel.

Meanwhile, in Spain, drivers saved up to 117% by charging instead of refuelling, while in Poland, the savings reached an impressive 170% by plugging in rather than filling up.

Although our analysis considers the average electricity price in each city, it’s crucial to remember that electric vehicles are largely charged during off-peak hours at night, making it cheaper for consumers who have different rates for day and night electricity usage.

In the long run, renewable energy represents the most affordable option.

The price increases that Europeans must consider stem from the continent’s overreliance on fossil fuels in general, particularly Russian gas.

A significant boost in renewable energy sources would be the ideal solution.

This approach would not only help to decrease electricity costs in the medium to long term but is also the only viable way for Europe to ensure its energy supply in an increasingly unpredictable geopolitical landscape.