When discussing electric buses, the statistics from China are remarkable. The “Electric Buses in Cities” report released by Bloomberg New Energy Finance in spring 2018 highlights this significant transformation. In 2016, China was registering 340 electric city buses daily. During the same year, Europe managed to put approximately 70 buses on the road each day, covering all types (urban, intercity, coaches) and fuel types combined. In this major shift towards adopting electric buses, Europe and the United States are mainly playing supporting roles.

Electric buses account for 17 percent of China’s circulating buses. According to Bloomberg New Energy Finance, by the end of 2017, there were 3 million city buses operating globally, with 385,000 classified as electric buses. Thus, the share of this category in the worldwide fleet stands at 13 percent.

However, this statistic is somewhat misleading. Nearly all of these vehicles are found in China. Therefore, it is more accurate to claim that in China, the proportion of electric buses among circulating city buses is already 17%. In other regions, we are still seeing very small figures.

In China, the sales jumped from 69,000 units in 2015 to 132,000 in 2016; however, 2017 saw a notable decline due to reduced subsidies, with 90,000 fully electric buses and 16,000 hybrid plug-in buses registered.

China’s plans for the electrification of public transport are quite ambitious. For example, by the end of 2017, Shenzhen aimed to achieve 100% electric buses in operation (totaling 16,500 buses), while Beijing set a target of reaching 10,000 by 2020, starting from 1,320 last year. In 2018, Guangzhou announced two tenders for battery electric buses, one for 3,138 and the other for 1,672, totaling 4,810 electric buses. BYD won the contract to supply 4,473 units. In September 2018, Yutong Bus announced that it had sold a total of 90,000 new energy buses across countries such as France, the UK, Bulgaria, Iceland, Chile, and China Macau, among others (Yutong’s overall sales volume, including all types of buses and coaches, exceeds 70,000 units annually).

According to data from the China Bus Statistics Information Union, despite an overall decline in the Chinese bus market, which fell by 13.5% in the first three quarters of 2018, 55,658 new energy buses were sold in China, showing over a 20% year-on-year increase. The Chinese bus market experienced an 11 percent decline in 2019 compared to 2018.

The largest electric bus order to date was signed in December 2020 with Yutong as the supplier, securing an unprecedented order of 1,002 buses (yes, that’s correct). Out of these, 741 will be electric, making it the biggest order for electric buses ever. This contract was awarded to Mowasalat, the public transport company in Qatar, which will provide services for the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022.

Chinese companies hold a third of the electric bus market in Europe, and local manufacturers are seeking increased EU involvement.

Automakers, governments, and the European Commission are becoming increasingly concerned about Chinese battery-powered vehicles, but there’s another growing transport concern: electric city buses.

European leaders convened last week with Chinese leader Xi Jinping, who completed a visit to France, Serbia, and Hungary on Friday. A significant point of tension during the visit revolved around the EU’s investigation into whether Chinese electric vehicles are being unfairly subsidized.

Last year, one-fifth of the electric vehicles sold in Europe originated from China, and the environmental NGO Transport & Environment anticipates that this percentage will rise to a quarter this year.

Similar worries surround the bus industry—that China might dominate the market using the vast scale of its domestic electric bus market and lower production costs to outcompete European manufacturers. However, at this time, Brussels is dismissing calls from the industry to investigate Chinese bus producers for unfair subsidies.

“Threats to industry competitiveness are arising from fierce global competition, with Chinese bus manufacturers already capturing market shares in the EU over recent years,” remarked Thomas Fabian, chief commercial vehicle officer of the EU car lobby ACEA.

The industry is undergoing rapid changes due to the EU’s pledge to ban the sale of CO2-emitting buses by 2035, alongside a target of 90 percent emissions reduction by 2030. This is boosting the demand for non-fossil-fuel buses, especially electric ones.

City buses are leading the electrification movement—unlike long-distance coaches, they operate on established routes, have shorter travel distances, and can be conveniently recharged, according to the International Energy Agency.

This is a sector where Chinese manufacturers are significant players.

According to Bloomberg, the latest global data on electric buses shows that in 2018, the number of these vehicles worldwide increased by 32 percent to approximately 425,000. Out of this total, 421,000, which is 99 percent, are located in China. Europe has around 2,250 electric buses, while the United States has a modest 300 in operation.

It is anticipated that the total number of electric buses in Chinese cities will rise to 611,000 by 2025, whereas the U.S. is projected to have about 4,750 and Europe around 12,000. Currently, an estimated 18 percent of all buses in China are electric.

China’s dominance can be attributed to several factors. The government has encouraged local authorities to transition to electric bus fleets and is providing substantial financial support. The environmental challenges faced by Chinese cities are another significant incentive, prompting the nation to take action. These initiatives also aim to bolster domestic manufacturers and prepare them for competition on a global scale. Additionally, many of the over 130 cities with populations exceeding one million are relatively young, lacking a historical reliance on combustion engine bus fleets and outdated bureaucracies.

In Europe and the U.S., purchases of electric buses have primarily been seen as supplementary to existing fleets rather than as replacements. Moreover, these regions lack comprehensive national plans that endorse the shift from combustion to electric bus fleets, and they do not offer significant subsidies to motivate cities and communities. However, the European Union mandates zero-emission vehicles starting in 2025.

Bloomberg additionally estimates that 1,000 electric buses can save 500 barrels of oil per day in imports. One challenge is the high initial cost of electric buses, which can be twice that of traditional buses due to battery prices. However, operating and maintenance expenses are generally lower. Manufacturers like Proterra in California offer battery leasing options to help mitigate upfront expenses.

BYD has marketed its electric buses in over 300 cities worldwide, including several European nations like Norway, England, and Poland.

Last year, the top 12 manufacturers in Europe sold 5,107 electric buses, with almost one-third produced by Chinese companies such as Yutong, BYD, and BYD’s partnership with Britain’s Alexander Dennis, along with Zhongtong, as highlighted in a report by Chatrou CME Solutions.

Chinese companies’ market share has decreased to 25 percent from 41 percent in 2022. This decline is attributed to an increase in electric bus production by MAN from Germany and Solaris from Poland, a subsidiary of Spain’s CAF.

Daimler Truck, a manufacturer of heavy-duty vehicles, characterized the bus industry as being highly competitive and sensitive to pricing.

The Chinese electric vehicle manufacturer BYD is becoming more influential. With ambitious plans for the electric vehicle market, BYD is a key player in the e-bus sector, operating factories in the U.K., the Netherlands, and Hungary.

In January, BYD secured a significant contract for 92 buses worth €43 million with De Lijn, a transit company owned by the Flemish government — a considerable loss for local manufacturers such as Van Hool and Dutch company VDL Bus & Coach. The agreement includes an option to provide a total of 500 buses in the future, potentially earning BYD €234 million.

Van Hool recently declared bankruptcy.

VDL accuses BYD of receiving substantial subsidies from the Chinese government. “To create a fair competitive landscape and address the imbalance, we have been urging the EU to take action for years,” stated VDL spokesperson Miel Timmers.

BYD has not replied to a request for comment.

According to ACEA’s Fabian, it is the responsibility of policymakers to ensure that bus manufacturers can continue “competing on a level playing field.”

Thus far, the European Commission has not launched its competition inspectors on the bus industry as it has on the much larger electric vehicle sector.

European manufacturers hope that Brussels will monitor the market closely.

“EU markets are open to any company that complies with European regulations. We trust that European competition authorities will ensure future fairness in competition,” stated a spokesperson from Volvo.

China’s BYD is set to initiate electric bus production in Azerbaijan

Electrify Azerbaijan Company and China’s BYD Company Limited (BYD) signed a framework agreement on Tuesday aimed at refreshing the passenger bus fleet in Azerbaijan.

This framework addresses the acquisition of electric buses, servicing arrangements, and the establishment and localization of electric bus production in Azerbaijan, according to Azertag. The final contract is expected to be finalized in September.

BYD has plans to invest $60 million in Azerbaijan, which will lead to the development of new production facilities for light-duty electric trucks, electric vehicles used for municipal services, and electric passenger cars starting in 2026, along with battery production for energy storage beginning in 2028. By 2025, BYD will also start local production of spare parts in Azerbaijan, with localization expected to cover 40 percent of the overall bus costs by 2030.

BYD emerged as the global leader in 2023, achieving record sales of 3 million new energy vehicles. The company is recognized for its advancements in automotive technology, electronics, electric batteries, renewable energy, and rail transport.

Initially, BYD plans to allocate $34 million for the electric bus production at a new facility in Sumgait Chemical Industrial Park, targeting an annual output of 500 units to cater to domestic requirements and export prospects. Once operational, the electric bus demand in Azerbaijan will be satisfied through local manufacturing.

In the meantime, “BakuBus” plans to acquire 160 electric buses and 100 charging stations from BYD, with intentions to have these buses operational in Baku by October 31, 2024.

The first BYD electric bus was launched in Baku in April 2023, followed by the addition of an electric passenger shuttle from the Chinese Yutong brand in December as part of a pilot mobility initiative.

From 2016 to 2023, over 61% of Baku’s passenger bus fleet has been upgraded, incorporating 1,044 modern medium and large-size shuttles, with 76% powered by LNG engines. The goal is to transition the entire fleet to electric buses by 2028.

The partnership agreement with BYD, signed prior to the upcoming United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP 29) in Azerbaijan in November, highlights Baku’s dedication to global climate change initiatives.

Azerbaijan reaffirmed commitments under the 2015 Paris Agreement to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 35 percent by 2030 and aim for a reduction of 40 percent by 2050.

Baku became a signatory to the 2015 Paris Agreement, a legally binding treaty regarding climate change, in April 2016 and has actively sought to address the prioritized issues set by the government since then.

The Paris Agreement establishes long-term goals to guide nations in substantially reducing global greenhouse gas emissions and limiting global temperature rise to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels. It emphasizes that countries should strive to limit the global temperature rise to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels to significantly mitigate the risks and impacts of climate change.

Additionally, it urges participating countries to frequently evaluate collective progress toward achieving the agreement’s objectives and long-term goals, as well as providing support to developing nations in their efforts to combat climate change and enhance resilience.

The Azerbaijani government prioritizes the shift from conventional energy sources to alternative energy. By 2030, it is anticipated that renewable sources will contribute 30 percent of Azerbaijan’s electricity generation. The estimated renewable energy potential for Azerbaijan is 37,000 MW, with 10,000 MW identified following the country’s territorial liberation from Armenian control in 2020.

Wind power is estimated to encompass 59.2 percent of Azerbaijan’s total renewable energy potential. Solar energy ranks second, amounting to 8,000 MW of potential. Additionally, biomass, geothermal, and hydropower (excluding major hydropower facilities) are regarded as promising renewable sources at 900 MW, 800 MW, and 650 MW, respectively.

Furthermore, the Azerbaijani government aims to fully convert the liberated regions of Karabakh (Garabagh) and East Zangazur into a “Net-Zero Emission” Zone as a key element of ongoing reconstruction and development efforts. The green energy opportunities in the liberated territories include nearly all forms of renewable resources, such as hydro, solar, wind, and geothermal.

China has taken the lead in the electric vehicle revolution – a movement that started with buses. In the 2010s, China implemented an extensive and rapid electric bus network. Today, China’s electric buses are not only impacting the nation’s electric vehicle growth but also that of the entire world.

On Nanjing Xi Lu, one of Shanghai’s busiest streets, two distinct types of electric buses can be seen in operation. The first is a group of blue trolleybuses operating along bus route number 20, established by a British transportation company in 1928. They draw electricity from overhead wires using poles on their roofs, maintaining this method for almost a hundred years.

While these historical trolleybuses symbolize Europe’s former technological advancements, the modern buses passing by represent China’s current ambitions for net-zero emissions.

These stylish electric buses, which run on lithium batteries instead of wires, began their rollout in Shanghai in large numbers starting in 2014. Unlike the once-common diesel buses that produced loud “vroom-vroom” noises and emitted dark smoke, the electric buses now dominating Shanghai’s streets are quiet, pollution-free, and visually appealing. They also provide a smooth ride, especially during acceleration and deceleration.

Although these elegant buses are now a common sight across much of China, their position as a green transportation symbol was not always guaranteed. As they travel along their busy daily routes, these vehicles are significantly influencing not only China’s swift electric vehicle transition but also the global landscape.

Initially, the government’s push for electric bus manufacturing and usage primarily focused on industrial advancement and addressing air pollution. It wasn’t until the government’s commitment in 2020 to attain carbon neutrality by 2060 that the promotion of electric vehicles became integral to its climate strategies. Nevertheless, this approach seems to be effective.

China now holds the title of the largest market for electric buses globally, accounting for over 95% of the worldwide total. According to the latest data, in 2018, China was the second-largest contributor to carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions within the global transport sector, responsible for 11%, trailing only the United States, which contributed 21%. To help reduce transport-related emissions worldwide, the International Energy Agency has advocated for policies that promote public transport and electric vehicles – and China’s rollout of electric buses is facilitating both.

After approximately two decades of government backing, China now features the world’s largest e-bus market, comprising more than 95% of the global inventory. By the end of 2022, China’s Ministry of Transport reported that over three-quarters (77% or 542,600) of all urban buses in the nation were classified as “new energy vehicles,” a term the Chinese government uses to describe fully electric buses, plug-in hybrids, and fuel cell vehicles that utilize alternative fuels such as hydrogen and methanol. In 2022, about 84% of the new energy bus fleet consisted of pure electric buses.

The pace of this transition has been impressive. In 2015, 78% of urban buses in China were still utilizing diesel or gas, according to the World Resources Institute (WRI). The NGO now estimates that if China adheres to its declared decarbonization policies, its road transport emissions will peak prior to 2030.

Additionally, China is home to some of the largest manufacturers of electric buses in the world, including Yutong, which has been receiving orders from regions across China, Europe, and Latin America.

“China has truly led the way in transitioning all types of vehicles, particularly buses, to electric,” states Heather Thompson, CEO of the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), a non-profit organization focused on sustainable transportation solutions. “While other parts of the world are striving for similar advancements, I believe China is significantly ahead.”

So, what enabled China to achieve this leading position?

A new direction

When China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, the global automotive market was predominantly controlled by European, American, and Japanese car manufacturers, who had invested many years refining internal combustion engine technologies. In order to compete, Beijing opted to pursue a different path for its automotive sector: producing cars that utilized alternative energy sources.

That same year, the central government initiated the “863 plan,” aimed at research and development for electric vehicles (EVs). However, there were several practical obstacles to mass electrification, including a limited number of manufacturers producing new energy vehicles, a small customer base, and insufficient charging infrastructure. The solution? Buses.

“The Chinese government implemented a very intelligent strategy,” explains Liu Daizong, ITDP’s East Asia director. “They recognized early on that they could lead the EV industry by focusing on electric buses,” he says, noting that their public service nature allowed Beijing to exert significant influence over their electrification.

There were also technological justifications for prioritizing buses in the transition to electric vehicles. “Bus routes were set and predictable. This allowed an electric bus to come back to its base for recharging after completing its route,” clarifies Xue Lulu, a mobility manager at the World Resources Institute (WRI) China. The average daily distance covered by a Chinese bus—200 km (120 miles)—was a feasible target for battery manufacturers.

Expanding the network

China first exhibited its international electric vehicle aspirations during the 2008 Olympics in Beijing, where a fleet of 595 “green” vehicles, provided by the Ministry of Technology, transported athletes, guests, and spectators between venues.

In the following year, the country launched a large-scale deployment of new energy buses with the “Ten Cities and Thousand Vehicles” initiative. The aim of this program was to support 10 cities with financial incentives to promote 1,000 public-sector new energy vehicles in each city annually over three years. The objective was to achieve a 10% share of new energy vehicles in the nation by the end of 2012.

Strong support from both central and regional governments “instilled confidence in manufacturers to establish production lines and enhance research initiatives,” asserts Liu.

By the conclusion of 2012, the program expanded to 25 cities, leading to the deployment of 27,432 new energy vehicles, as reported by China Auto News, a publication associated with the state-owned People’s Daily Group. Additionally, the central government created a technological innovation fund to stimulate research and development in the energy-saving and new energy automotive sector, as noted by the publication. By December 2013, this fund had allocated a total of 1.6 billion yuan (£179 million/$226 million) to 25 projects from 24 companies.

These coherent and strong governmental signals encouraged Chinese manufacturers to increase their EV production capabilities, reduce costs, and enhance their technologies. One notable company was Build Your Dream, commonly known as BYD. This Shenzhen-based company, which became the world’s largest EV manufacturer in 2022, significantly expanded its operations a decade earlier by supplying electric buses and taxis for China’s pioneering EV cities.

Making it personal

The advancement was not without challenges. The “Ten Cities, A Thousand Vehicles” initiative initially fell short of its goal, missing the three-year target of 30,000 vehicles due to insufficient interest from cities. However, another factor began to motivate cities to adopt new energy buses: air pollution.

“At that time, most buses were powered by diesel, which contributed significantly to nitrogen oxides (NOx) emissions,” states Xue, referencing the air pollution that afflicted Beijing and other Chinese cities in the early 2010s. Nevertheless, in 2013, a new central government plan identified air pollution as a contributing factor for the promotion of EVs.

This addition turned out to be crucial because it linked the adoption of electric vehicles to public health and indirectly associated the electric bus initiative with the political performance of local officials, since the central government would soon set air quality goals for all provinces.

In Lvliang, a small urban area situated in the coal-rich Shanxi Province, electric buses began to appear on the streets around this time, as noted by Wang Xiaojun, who was raised in the city and now resides in the Philippines, where he operates an NGO called People of Asia for Climate Solutions. “During the 80s and 90s, Lvliang had no buses at all; only vehicles used for coal transportation existed. Most people walked everywhere,” he states. As Lvliang began to develop, the local government established bus routes that initially utilized oil-fueled buses, but by 2013, many of these were supplanted by electric versions, “most likely due to the pressure [the local government] faced regarding air pollution.”

The years 2013 and 2014 were significant for China’s electric vehicle (EV) initiative. For the first time, the central government provided purchase subsidies for EVs to individual consumers rather than just the public sector, which opened the door to private ownership. Moreover, it offered reduced electricity rates for bus operators to ensure that the costs associated with running electric buses would be “considerably lower than” those of their gasoline or diesel counterparts.

This new economic momentum, along with the local government’s resolve to combat air pollution, created substantial enthusiasm for electric buses. By the end of 2015, the count of EV pilot cities surged from 25 to 88. In that same year, the central government set a goal of having 200,000 new energy buses on the roads by 2020 and revealed a plan to phase out subsidies for fossil-fuel-powered buses.

To further boost the market, numerous cities implemented various local policies in addition to national incentives. For instance, Shenzhen, a city in the south with over 17 million residents, encouraged government bodies to partner with private firms to develop a comprehensive array of rental options for bus operators. The battery constitutes 40-50% of an e-bus’s overall cost, making such rental programs vital, explains Liu from ITDP. In this approach, a bus operator could lease a battery from a manufacturer via a third-party financial organization and pay the rent with savings accrued from not using pricier diesel or gasoline.

Different bus operators in different cities also created varying charging strategies. “Buses in Shenzhen came with larger batteries, so they typically charged overnight,” notes Xue from WRI China. Between 2016 and 2020, Shanghai, another hub for electric buses, provided subsidies for the electricity used by electric buses, regardless of the charging time, to offer more flexibility in their charging schedules.

However, the generous financial support did lead to complications. In 2016, a scandal regarding EV subsidies rocked China, with some bus operators found to have inflated the number of e-buses they claimed to have bought. Consequently, that same year, Beijing revised its subsidy rules for electric vehicles, dictating that bus operators could only access financial support after a bus had traveled 30,000 km (19,000 miles).

In the following year, the government introduced the “dual-credit” policy. This allowed manufacturers of new energy vehicles to accumulate credits that could be sold for cash to those needing to balance out “negative credits” resulting from conventional car production.

Due to these policies, by 2017, Shenzhen had become the first city in the world to convert all of its buses to battery-powered vehicles — a 2021 study indicated that this transition had “significantly reduced” both greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution in the region.

The expansion of electric buses in China appeared to be on an unstoppable trajectory. The market was growing so rapidly that in 2018, the government revised its 2020 target for new energy buses from 200,000 to 400,000 and decided it was time to begin gradually eliminating the subsidies.

Every 2.5 of China’s 13.1 million new energy vehicles corresponds to one charging pillar. Additionally, it was not only China’s buses that gained from this initiative; the e-bus campaign contributed to the establishment of a large and stable market for the broader electric vehicle industry, drove down costs, and created economies of scale. In 2009, when the e-bus initiative began, the total sales of new energy vehicles were recorded at 2,300; by 2022, this number had increased to 6.9 million, as suggested by analysis from Huang Zheng, a researcher at the Institute for Internet Industry at Tsinghua University.

By 2022, the country had also constructed the largest EV charging network globally, featuring 1.8 million public charging stations — comprising two-thirds of the global total — and 3.4 million private stations. This translates to an average of one charging pillar for every 2.5 of China’s 13.1 million new energy vehicles.

However, thus far, the Chinese cities that have achieved the most effective deployment of electric buses—such as Shenzhen, Beijing, and Shanghai—tend to experience moderate weather and have relatively flat terrains. In order to elevate the e-bus initiative to a higher level, China faces several hurdles.

For one thing, bringing fleets to cities like Hong Kong, which, similar to London, have double-decker buses, is challenging. These two-story vehicles are “very difficult” to electrify, as Xue describes, because they are heavier, consume more energy, and thus require larger batteries, which reduces the passenger capacity. One of the rare electric double-decker models is produced in collaboration between BYD and ADL, a bus manufacturer from the UK.

Cold weather poses a challenge as it can prolong charging times for batteries and diminish their range. According to Xue, the reason China has not achieved complete electrification of its buses is due to the severe winters experienced in its northern regions.

Another issue is that the current manufacturing process for electric buses can produce pollution and be emissions-heavy, according to Wang; this includes everything from the mining of raw materials for batteries, such as nickel and lithium, to steel production. The steel industry is particularly tough to decarbonise because of its reliance on coking coal, which is essential for generating high temperatures and serves as a chemical reactant.

To ensure that electric buses are genuinely “green,” they ideally need to be powered by renewable energy, states Wang. However, last year, coal power still represented 58.4% of China’s energy mix, as reported by the China Electricity Council, a trade association.

In a global context, China has outpaced all other countries in the adoption of electric buses. By 2018, approximately 421,000 of the world’s 425,000 electric buses were in China, while Europe had around 2,250, and the US had roughly 300. As noted by Alicia García Herrero, a senior fellow at the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel, Europe has generally “lagged” in providing substantial fiscal support for electric buses.

Earlier this year, however, the European Commission set a target for all new city buses to be zero-emission by 2030. Moreover, several countries are boosting their overall funding for this transition.

In 2020, the European Commission approved Germany’s initiative to increase its support for electric buses to €650 million (£558 million/$707 million), and again in 2021, it was raised to €1.25 billion (£1.07 billion/$1.3 billion). Additionally, the UK, which had the largest fleet of electric buses in Europe last year with 2,226 fully electric and hybrid models, announced another £129 million ($164 million) to assist bus operators in acquiring zero-emissions fleets.

Though it may seem straightforward for other nations to initiate their electric bus programs with government subsidies, similar to China, a swift rollout also hinges on manufacturing capacity and infrastructure, remarks Ran Ze, a director at the China Representative Office of the Environmental Defense Fund, an international environmental advocacy organization. “This is something that many other countries, especially those in development, will struggle to replicate.”

Countries have therefore reacted to China’s manufacturing supremacy in various ways. “While the US has chosen a more competitive route by promoting its own electric bus production, regions like Latin America are more amenable to trade with China due to a more favorable trading framework through [China’s] Belt and Road Initiative,” explains Liu.

To avert direct competition from Chinese manufacturers, the US has initiated a “school-bus strategy,” according to Liu. Since the iconic yellow vehicles are not made by the Chinese, this could stimulate American electric bus manufacturing and foster a local industry chain. So far, this national initiative, supported by the US Environmental Protection Agency’s $5 billion (£3.9 billion) Clean School Bus Programme, has committed to providing 5,982 buses.

Conversely, numerous Latin American cities, including Bogotá, the capital of Colombia, and Santiago, the capital of Chile, are modernizing their traditional bus systems with the assistance of Chinese manufacturers, who are the major suppliers for the region. In 2020, Chile emerged as the nation with the highest number of Chinese electric buses outside of China, and this year, Santiago’s public transport operator announced an order of 1,022 electric buses from Beijing-based Foton Motor, marking the largest overseas deal the company has secured.

Chinese manufacturers are likely to receive even more orders from Chile and its neighboring countries throughout this decade. According to recent research by the global C40 Cities network, the number of electric buses in 32 Latin American cities is projected to increase more than sevenfold by 2030, representing an investment opportunity exceeding $11.3 billion (£8.9 billion).

Thompson, from ITDP, notes that many successful Latin American cities have also drawn inspiration from China’s financing methods, with electric companies participating in the expenses, “understanding that ultimately the buses will connect to their electricity grid,” she explains.

In Europe, Chinese electric bus manufacturers are expected to encounter growing challenges. Responding to China’s lead in electric vehicle production, EU lawmakers have initiated an anti-subsidy inquiry, following European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s statement that the global market is oversaturated with lower-cost electric vehicles.

“Amid the worldwide movement towards building more resilient supply chains, many nations are attempting to lessen their reliance on China,” García Herrero states.

The fast track to achieving net zero

In June 2023, BloombergNEF predicted that by 2032, half of the world’s buses will be fully battery-operated, a decade earlier than cars. Furthermore, by 2026, 36% and 24% of bus sales in Europe and the US, respectively, are projected to be electric vehicles, as they begin to catch up with China’s progress, according to BloombergNEF’s report. However, Thompson argues that global electrification of buses still has significant distance to cover, particularly in Latin America, Asia, and Africa.

“In regions like Africa, a substantial number of buses operate on the streets, but they aren’t integrated into the formal public transport systems,” she observes. “These are small minibuses that likely originated in European or Japanese markets before being sent to Africa.”

To achieve the global climate objectives outlined in the Paris Agreement, merely substituting the planet’s existing bus fleets may not suffice. ITDP suggests that the total greenhouse gas output from urban passenger transport worldwide must remain below 66 gigatonnes CO2 from 2020 to 2050 to reach the 1.5°C temperature target. Meeting this emissions cap will depend on not just the adoption of electric buses, but also a broader transition away from private transportation.

“We cannot solely concentrate on [replacing] the current buses; we must significantly increase the number of buses on the roads,” Thompson emphasizes. She and her team estimate that by 2030, around 10 million additional buses will be required, resulting in a cumulative need for 46 million more buses by 2050 to ensure public transportation is sufficiently effective to help fulfill the Paris Agreement. And all these buses will need to operate on electricity.

In China, while electric vehicles are being sold at unprecedented rates, the central government has directed cities to promote the use of public transportation, along with walking and cycling.

Outside residential complexes in the megacity of Shanghai, vibrant posters featuring an electric bus, a bicycle, and a subway train encourage passersby to adopt low-carbon commuting options. The main bus service provider in another city, Heze, which has nearly nine million residents, has also reportedly agreed to modify bus routes based on the needs of citizens, such as by including stops at schools.

In Wang’s hometown, which has just over three million inhabitants, the local authorities have taken an additional step by making all bus rides free of charge. Citizens simply need to swipe an app to board the bus at no cost. “My aunt loves riding the buses now,” Wang shares. “She finds it very convenient.”

Wang now feels that despite the pollution caused by manufacturing electric buses, enhancing their accessibility is the appropriate direction for both China and the globe.

“Only then can [the government] progress to the next phase—ensuring that the electricity sources, batteries, and steel used for the buses are more environmentally friendly moving forward,” he adds.

China continues to be a leading player in the global electric vehicle (EV) market, with the latest information from consulting firm Interact Analysis providing insights into the nation’s electrified commercial vehicle sector for 2023.

Geely stands out as a key player in the new energy field, dominating both the truck and bus segments. In 2023, Geely’s sales soared to nearly 75,000 electrified trucks and buses, a threefold increase compared to its nearest rival, Chery Group, according to Senior Research Director Alastair Hayfield’s post on LinkedIn. While Chery and Foton Motor saw advancements in their market positions, Dongfeng Automobile Co., Ltd. witnessed a decrease in market share.

There are 160,000 new energy buses in China in 2023.

Focusing specifically on new energy buses (refer to the chart below), Geely, Chery, and Chang’an Auto have largely led the market due to the popularity of small-sized electric buses. Foton ranked fourth with 15,000 units sold, King Long sold nearly 9,000 e-buses, while Yutong finished in ninth place with 5,200 buses. When solely considering large-sized buses, King Long, Foton, and Yutong have taken the top spots. The overall market for new energy buses in China is estimated to be around 160,000 units in 2023.

According to Hayfield’s post, the report emphasizes strong market engagement: “In 2023, 70 OEMs sold new energy buses, and the top 10 companies accounted for 87.6% of total sales, which is an increase of 6.8 percentage points year-on-year. Geely topped the list with a year-on-year growth of 112%, securing a market share of 26.6%. Chang’an Auto achieved the fastest growth among the top ten, earning the third position thanks to its strong sales of small-sized buses.”

Manufacturers

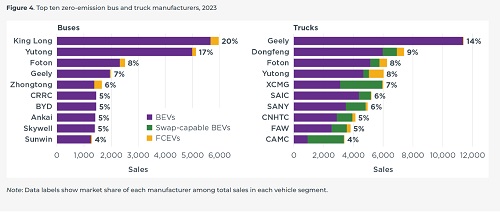

In the zero-emission (ZE) bus and truck markets, the top ten manufacturers represented 82% and 72% of total sales, respectively. Among bus producers, King Long (20% of total ZE bus sales) and Yutong (17%) maintained a significant lead. King Long also excelled in sales of fuel cell electric buses, followed closely by Zhongtong. In the ZE truck market, Geely led in overall sales, with Dongfeng and Foton following. While most leading ZE truck manufacturers employed various technologies, nearly all of Geely’s sales stemmed from battery electric vehicles (BEVs). Yutong was at the forefront in sales of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), while XCMG led in swap-capable BEV sales.

In 2023, 39% of battery electric bus sales and 53% of battery electric truck sales were concentrated in the top ten cities for each segment. Cities like Shenzhen, Shanghai, Chengdu, and Beijing ranked among the top ten for sales in both vehicle categories. Chinese cities have implemented different strategies to enhance the uptake of zero-emission trucks. For example, starting in 2021, Tangshan—home to significant ports and a hub for steel production—was designated as a pilot city for developing swap-capable trucks under the national program. Chengdu has incentivized the adoption of zero-emission engineering and dump trucks through measures such as preferential access to roads. Six of the ten cities with the highest sales of ZE buses and trucks are located in regions subject to the aforementioned pollution control policies.

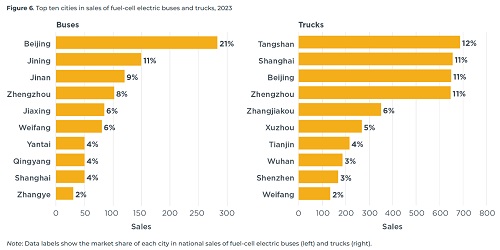

The ten cities with the highest sales of fuel-cell electric buses and trucks in 2023 accounted for 75% and 68% of each market, respectively. In 2020, the national government initiated a pilot program to demonstrate FCEVs in urban areas, and five city clusters—Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Shanghai, Guangdong, Hebei, and Henan—were selected for this initiative. In 2023, six of the top ten cities for fuel-cell electric bus sales and eight of the top ten for fuel-cell electric truck sales were part of these FCEV pilot clusters. Among non-pilot cities, Jining and Jinan, which rank as the second- and third-largest markets for fuel-cell electric buses, are both located in Shandong Province, a designated region for hydrogen research and application since 2021. Jinan is also home to the headquarters of CNHTC (commonly known as Sinotruk), a notable manufacturer of heavy-duty vehicles and zero-emission heavy-duty vehicles. The top four cities for fuel-cell electric truck sales remained unchanged from 2022.